This is an interesting question. The plagal of the third mode has been called varys (which means heavy, deep, or grave), even in the oldest surviving chant manuscripts from the first millenium. The reason is probably lost to time, as none of the surviving ancient theoretical treatises give an explanation, so one can only guess.

One such guess is put forth in Chapter X of the Great Theory of Music by Chrysanthos. My simplified explanation for those with a background in Western music notation is below.

Originally, the base of the first mode was what we would now call Ke, or A, to use Western conventions. To "find Ke", one started at Dhi, or G, and went up a whole tone to Ke, singing the syllables "ananes". That is, one starts at G and ascends to A, and this is the first "sound", or "mode" as we now call it. From there, a pentachordal scale called "the wheel" was used. This scale is (approximately) Tone, Tone, Semitone, Tone.

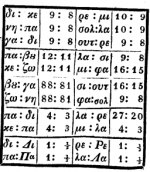

The first five notes of the scale then become the following, using Western note names.

G A B C D

Then, being a pentachordal scale, the scale repeats itself starting from D. This gives the following scale.

G A B C D E F# G A

So looking at this scale so far, it appears to be the diatonic octave scale in G. This is because, thus far, it just so happens that the notes of two conjunct pentachords is the same as that of the octave system.

But how do we descend in this scale below the base note of G? If this were an octave scale, we would descend to F#, giving

F# G A B C D E F# G A

But this is not an octave scale. It is a pentachordal scale and we actually descend a whole tone to F.

F G A B C D E F# G A

Descending the full pentachord gives

C D E F G A B C D E F# G A.

So to find the "grave mode", one starts at G and descends a whole tone. Because this tone "pulls us down" farther than we would have if we were using the octave scale, the note is called "heavy".

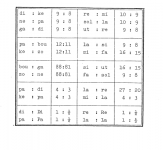

In this ancient system, you find the authentic "sounds" or "modes" by going up from G, and you find the plagal "sounds" or "modes" by going down from A. So starting at G, you go up one note in the scale to find A, the first sound. B is the second sound. C is the third sound, and D is the fourth sound. Going down from A, G is the plagal of the fourth, F is the plagal of the third, E is the plagal of the second, and D is the plagal of the first.

In those times, there was little or no distinction between a "note", a "tone", a "sound", or a "mode". That is, Ke, or A, was simply the "first sound", which denoted not only the note in the scale, but also the entire "mode" as we would now call it. So the "heavy sound" was the "heavy mode" because its base was found by "finding the plagal of the third", or rather "finding the heavy sound".