Shota

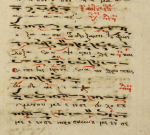

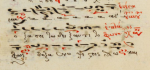

Παλαιό Μέλος

2) "We cannot judge by today's repertory to conclude what was the repertory of the Constantinopolitan chanters in the 19th c.".

Well, if you did not have the opportunity to speak with the psaltae of old time, this might be a potential statement that one could propose. The psaltae of old-time are very clear about what they were taught and what they saw "in action" at the analogion in the late 1800s, early 1900s and that is nothing more than the classical music. The Patriarchal Church was a different matter altogether and even more conservative and strict...The Axion Estin, and Kalophonic hymn material in Nektarios is largely a compilation of "mathimata", and even the monasteries of Athos did not use them all (my personal discussions with the late-blessed Fr. Panaretos of Philotheou).

To give just a little example, are Gerasimos Kanellidis' Leitourgika "classical music"? Would Neleus Kamarados chant only "classical music"?

Already with a quick search one can find a sufficient number of Athonite Axion esti recordings from Nektarios' books, e.g. Filanthidis' Axion esti in Deuteroprotos (Karcigar), the one composed by Anastasios from Parla in Pl. 4, the one by Charalampos Papanikolaou in Pl. 4, the anonymous composition in Pl. 2 and so on. The point is that execution of these melodies requires technical skill and not all Athonites have it. Those that don't have it, also don't chant them (more difficult ones, at least), I presume (in his teaching recording of the Leitourgika in Plagal First by Kanellidis edited by A. Kyriazidis (and of Sarantaekklesiotis' Axion esti in Pl. 1), Fr. Daniel of the Danielaioi brotherhood characteristically remarks that these Leitourgika are πολύ ωραία, but θέλουν μονάχα λίγο μελέτη περισσότερα. That's an Athonite way of saying what is reachable for somebody with a modest musical talent and what is not, I guess

3) "that the older repertory got displaced by newer compositions by Kamarados, Hatziathanasiou, Palasis, Pringos, Stanitsas etc.".

This is true. But this phenomenon became de riguer in Athens largely. Constantinopolitan churches were more conservative.

All the composers I named were Constantinopolitans. And I don't see the point in arguing that their compositions were chanted in Constantinople, because they were (as a little anecdote, (narrated in Tsiounis' book on Stanitsas, I believe) upon becoming Lampadarios at the Patriarchate, Stanitsas got asked by his friends from his Palasis times why he wouldn't chant some mathemata of his teacher, to which he responded (quoting from the memory): "Forget those senseless things. The music is the one we chant at the Patriarchate").

4) Concerning Nicholas of Smyrna: Much of his compositions remained mathimata and were never used in churches in services (personal communication of Matthaios Andreou, student of Vamvoudakis).

Composers/chantors were very careful in introducing new music in the service, however, from the standpoint of teaching, they did not shy from melodies that incorporated elements of Ottoman music/rhythms.

Consider again how much of all this repertory was actually used in churches up until the 1970s. And even today, how many times does one hear Nicholas of Smyrna Cherubic hymns in church practice?

I guess there is no point in doubting that Nikolaos and his successor Misailidis would use Nikolaos' books at the analogion. Now many of Nikolaos' compositions are indeed long mathemata, but others are not and in any case all his compositions bear his distinct style. And when talking about Nikolaos' work, I didn't mean only his Liturgy volume, as you perhaps thought, but also his other books. As far as who would chant what, e.g. every year in Patras the late Metropolitan Nikodimos would use many compositions from Nikolaos' books for Doxastika and Idiomela, especially during the Holy Week period. About Nikolaos' papadic Liturgy pieces: these were chanted where

1) circumstances would allow it (enough time);

2) students of Nikolaos were active;

3) papadic melos hasn't degenerated into improvisation, or displaced completely in favour of other compositions as in the case of the koinonika.

Up until some time ago Athos was such a place, but I guess there too Nikolaos' compositions are destined to eventually disappear.

P.S. When Vamvoudakis included in his book polyphonic pieces (in Byzantine notation) by Bortnyanski, did he do it for training purposes? Or when Andreou chanted Sakellaridis in Canada? The chanters don't live in lab conditions, they adapt or get influenced by the environment, and what was the musical aesthetics of Smyrni is attested by numerous early 20th c. recordings. And that that did influence the Smyrni yphos is something that already Boudouris sensed.