Όμηρος

Κεντεποζίδου Ελένη

Ο Béla Bartόκ ως εθνομουσικολόγος

ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑΣ

ΤΜΗΜΑ ΜΟΥΣΙΚΗΣ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΕΧΝΗΣ

ΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΗ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ

2008

''Το 1940 ο Bartόκ μετανάστευσε με τη γυναίκα του στις Η.Π.Α.. Εκεί ο Dr. Herzog

στο πανεπιστήμιο της Κολομβίας του πρότεινε να μελετήσει μία μεγάλη συλλογή

ηχογραφήσεων (περίπου 2500 δίσκοι) που έγιναν στη Γιουγκοσλαβία το 1934-1935

από τον Milman Parry, καθηγητή κλασικής φιλολογίας του πανεπιστημίου του

Χάρβαρντ. Δεν είχε γίνει συστηματική μελέτη αυτού του υλικού μέχρι τότε, αφού ο

συλλέκτης του πέθανε λίγο μετά την επιστροφή του. Το μεγαλύτερο μέρος των

δίσκων ήταν αφιερωμένο στο ηρωικό έπος της Γιουγκοσλαβίας. Αυτό ήταν που

ενδιέφερε τον Parry. Ο στόχος του ήταν να ανακαλύψει την σχέση της Ηλιάδας και

της Οδύσσειας με τα σημερινά βαλκανικά λεγόμενα «αντρικά τραγούδια». Πίστευε

ότι είχε αναπτυχθεί μία μεγάλη παράδοση προφορικής ποίησης αυτών των έργων που

υπήρχε ακόμα στα Βαλκάνια. Αλλά μεταξύ αυτών υπήρχαν και περισσότεροι από 200

δίσκους με σερβοκροατικά «γυναικεία τραγούδια» με λυρικό χαρακτήρα και μουσικά

πιο ενδιαφέροντα. Ο Bartόκ επέλεξε να ασχοληθεί με αυτό το τμήμα της συλλογής

και να το προετοιμάσει για έκδοση. Ασχολήθηκε ωστόσο και με τα επικά τραγούδια

της Γιουγκοσλαβίας, γεγονός που είναι γενικά άγνωστο26.

Εκεί είχε ένα δωμάτιο στη διάθεσή του και δούλευε χωρίς καμία επίβλεψη. Σε ένα

γράμμα του προς τον Zoltàn Kodàly περιγράφει την κατάσταση ως εξής:

«Είχα πλήρη ελευθερία να διαλέξω τι είδους δουλειά να κάνω. Διάλεξα να

μεταγράψω τη μουσική σημειογραφία της συλλογής του Parry. Δουλεύω τώρα σε μία

πτέρυγα του πανεπιστημίου της Κολομβίας, στα φωνογραφημένα αρχεία του Herzog.

Ο εξοπλισμός είναι άψογος. Νιώθω σχεδόν σαν να συνεχίζω το έργο μου στην

ουγγρική επιστημονική ακαδημία, σε ελαφρώς διαφοροποιημένες συνθήκες. Όταν

διασχίζω την πανεπιστημιούπολη το βράδυ, νιώθω σαν να διασχίζω την ιστορική

πλατεία μιας ευρωπαϊκής πόλης.27»

Η δημοσίευση των αποτελεσμάτων της έρευνας του Bartόκ καθυστέρησε για αρκετά

χρόνια. Αν και ο πρόλογος του βιβλίου του, Serbo-Croatian Folk Songs, αναφέρει ότι

εκδόθηκε το Φεβρουάριο του 1943, στην πραγματικότητα δεν είχε εκδοθεί μέχρι το

Σεπτέμβρη του195128.

25Antokoletz, Fischer, Suchoff,2000

26Stevens,1993

27Demény,1971

28 Stevens,1993

20

Ο Bartόκ λαμβάνοντας υπόψη του το γεγονός ότι αυτή η μουσική διαδιδόταν

προφορικά, υποστήριζε ότι το δυτικό σημειογραφικό σύστημα ήταν ανεπαρκές για να

καταγραφεί αυτή η μουσική και υποδείκνυε ότι πρέπει να δημιουργηθούν «οπτικές

εντυπώσεις με συμβατικά σύμβολα δραστικής απλότητας» προκειμένου να μελετηθεί

το ηχητικό φαινόμενο. Μόνο το τονικό ύψος και ο ρυθμός μπορεί να σημειωθεί. Η

ένταση και ο χρωματισμός μπορούν να παραλειφθούν. Ευτυχώς, η ένταση δεν είναι

ένας σημαντικός παράγοντας για την μουσική της ανατολικής Ευρώπης. Αναφέρει

χαρακτηριστικά : «Σκοπός του εκτελεστή είναι να επιτύχει ομαλότητα. Πολύ σπάνια

ακούμε νότες τονισμένες από πρόθεση ή ομάδες από νότες να παράγονται με αλλαγές

των δυναμικών.»

Όσον αφορά τις κλίμακες, ο Bartόκ παρατήρησε ότι η πλειοψηφία των μελωδιών των

ηρωικών έπων έχουν μικρή τονική έκταση, αποτελούνται δηλαδή από τεμάχια

κλιμάκων από τέσσερις ή πέντε τόνους, τα οποία πιθανότατα να προέρχονται από

κάποιο αρχαίο σλαβικό στυλ.

Πιο σημαντική όμως είναι η σχέση μεταξύ της τονικής έκτασης και της καταληκτικής

νότας. Το 1926, ο Bartόκ παρατήρησε ότι ένα από τα κυριότερα χαρακτηριστικά της

σέρβικης μουσικής είναι η τονική έκταση ενός μείζονος εξαχόρδου, όπου η πρώτη,

τρίτη και η πέμπτη νότα αντιπροσωπεύουν τις κύριες βαθμίδες και η δεύτερη

βαθμίδα χρησιμοποιείται ως την “tonus finalis”. Στο βιβλίο του Yugoslavian Folk

Music29 , επεκτείνει αυτή την παρατήρηση, λέγοντας ότι: «ορισμένες βαθμίδες ,

κυρίως η δεύτερη και η τρίτη είναι αντικείμενα μεγάλης διακύμανσης σε τέτοιο

βαθμό που κάποιες φορές είναι αδύνατο να καθοριστεί αν η κλίμακα είναι ελάσσονα

ή μείζονα. Οι ουδέτερες βαθμίδες είναι άφθονες. Βρίσκουμε συχνά ομάδες που

αντιπροσωπεύουν τρεις ή τέσσερις κλίμακες.»

Ανακάλυψε επίσης ότι κάποιες κλίμακες περιέχουν το διάστημα της δευτέρας

αυξημένης, το οποίο μπορεί να εμφανιστεί μεταξύ της δεύτερης και της τρίτης

βαθμίδας (λα ύφεση- σι αναίρεση) ή μεταξύ τρίτης και τέταρτης βαθμίδας (σι ύφεση-

ντο δίεση). Ο Bartόκ υποστηρίζει ότι αυτά τα διαστήματα ίσως είναι σημάδια

αραβικής επιρροής, μέσω τουρκικής μεσολάβησης. Όσον αφορά τις χρωματικές

αλλαγές που επηρεάζουν τη δεύτερη και την τρίτη βαθμίδα, μπορεί να εμφανίζονται

σα φυσικές ή ελαττωμένες στην ίδια μελωδία. Οι δύο αυτές φόρμες, δεν είναι

αλληλένδετες, δεν είναι μία χρωματική ποικιλία όπως στη δυτική μουσική.

Στις γραπτές αναφορές του για τα επικά τραγούδια, ο Bartόκ υποστηρίζει τα

ευρήματα του γλωσσολόγου Roman Jakobson για τις ρυθμικές ιδιότητες των

σερβοκροατικών δεκασύλλαβων επικών στροφών, αλλά με τροποποιήσεις που

επιτρέπουν ρυθμικές παρεκκλίσεις. Η δομή της στροφής παραβλέπει εντελώς την

φυσική διάρκεια των συλλαβών, αλλά συγκεκριμένες στροφές των ηρωικών

ποιημάτων τραγουδισμένα σε τέμπο parlando-rubato επιτρέπουν «στομφώδη»

29Bartόκ,1951

21

τονισμό, δείχνοντας τον τρόπο, με τον οποίο η μελωδία προσαρμόζεται στο ρυθμό

και την κλίση της γλώσσας.

Μεγάλα διηγήματα των Σλάβων παρουσιάζονταν μέχρι πρόσφατα με δύο

διαφορετικά όργανα: το gusle και τον ταμπουρά. Ηχογράφησε τα τραγούδια με το

όργανο gusle, και οι μεταγραφές του είναι συνοπτικές. Αυτό το έκανε επειδή

μετέγραψε μόνο τις μελωδίες που είχαν κάποια διαφοροποίηση ή παραλλαγή. Τις

υπόλοιπες τις συνταύτισε σαν όμοιες με τον έναν ή με τον άλλο μελωδικό τύπο.

Το gusle, ένα μονόχορδο όργανο με δοξάρι, παίζεται από τον τραγουδιστή κατά τη

διάρκεια ολόκληρης της απαγγελίας του. Πρελούδια και μικρά συνδετικά περάσματα

μεταξύ των στροφών παρουσιάζονται παίζοντας μόνο το όργανο αυτό καθώς και

κατά τη διάρκεια του τραγουδιού, το gusle ενισχύει τη μελωδία με ταυτοφωνία ή με

μικρές ετεροφωνικές παρεκκλίσεις. Τα σημεία που το όργανο παίζει σόλο είναι

αυτοσχεδιαστικά με περάσματα που είναι χαρακτηριστικά του οργάνου.''

Bartόκ Β., Serbo-Croatian Folk Song, Columbia University Press, New York,

1951

Bartόκ B., Béla Bartόκʼ s Essays, University of Nebraska Press, London, 1992

Ο Béla Bartόκ ως εθνομουσικολόγος

dspace.lib.uom.gr/bitstream/2159/.../1/KentempozidouPE2008.pdf

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Homer.

Greek poet. He is thought to have lived during the 8th century BCE, in various coastal cities of Ionia.

1. Homer and music.

The two great epic poems ascribed to Homer clearly indicate that some kind of singing originally constituted their normal method of performance. Throughout the entire classical period from at least the time of Hesiod onwards, the Homeric poems themselves were recited, not sung. Their vocabulary includes neither kithara nor lyra; to designate the massive four-stringed lyre shown in early vase paintings, the term phorminx is regularly used. Auloi, which are mentioned only twice (Iliad, x.13; xviii.495), had apparently not yet become accepted on the Greek mainland.

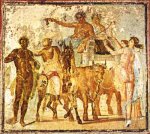

The role given to music in the Iliad is very different from that given in the companion poem, the Odyssey. Performers and audiences are quite simply absent: professionalism has either not yet appeared or not been allowed a place within the epic. The term aoidos, used frequently throughout the Odyssey as ʽbardʼ, occurs rarely in the Iliad (see Aoidos). There it clearly means ʽsingerʼ, with the specific sense of ʽmournerʼ. In every case, the characters of the Iliad make their own music. Thus when Odysseus and the other envoys come to Achillesʼ tent, they find him singing to his own lyre accompaniment (ix.186–9). Since the musical activity of the Iliad is normally communal, his behaviour on this occasion may reflect his profound sense of alienation. In its musical significance, one of the most important passages in the Iliad is the description of the ʽShield of Achillesʼ (xviii.478–607), fashioned by Hephaestus at Thetisʼs request for her son, Achilles. On the shield were depicted the singing of a hymenaios, a solo singer with a dancing chorus, other types of dances, and musical instruments such as the aulos and phorminx. This section of the Iliad provided the model for the Hesiodic ʽShield of Heraclesʼ (see Hesiod).

The Odyssey, by contrast, may be called the bardʼs poem. Now the singer of tales appears as a specialist; the term dēmioergos marks him as such, setting him apart. He is an awesome figure, to be treated with deference. Still, he has become a professional, and now a theme for singing may be suggested by his hearers or even objected to – an unthinkable occurrence within the Iliadʼs world of musical values. The bard nevertheless is very generally held in honour; the epithet theios (ʽgod-likeʼ) regularly attaches to him. He himself maintains that he has learnt his art from no mortal teacher; he is self-taught and performs under divine inspiration (xxii.347–8). Listeners may be so profoundly moved by his powers that they reveal their secret feelings, as Odysseus does when he hears the bard Demodocus (viii.84–92). The affective force of vocal music in other contexts always receives recognition from Homer; his Sirens employ song as a fatal lure; the enchantress Circe is a singer. Finally, there is the poetʼs awareness (e.g. in Iliad, ix.186; Odyssey, viii.580) that through the fame of sung words men may live on after death.

Warren Anderson/Thomas J. Mathiesen

2. Later treatments.

The characters of the Iliad form the staple of Greek tragedy, and Aeschylus is said to have described his own plays as ʽslices from the great banquet of Homerʼ. The Iliad, however, dealing with the end of the Trojan War, has proved less attractive to musicians than the Odyssey, which treats of the return to Ithaca of Odysseus (Ulysses). The most ambitious project to involve both epics has been August Bungert's plan for nine Homerische Welt operas, five concerning the Iliad and four the Odyssey. Only Achilleus and Klytämnestra were completed for the former set; the latter became Die Odyssee (1898–1903), comprising the separate Kirke, Nausikaa, Odysseus' Heimkehr, Odysseus' Tod. More modest have been the Homerische Symphonie of Lodewijk Mortelmans (1896–8) and a dance opera of the same title by Theodor Berger (1948).

Further operas inspired by the Iliad include José Nebra's Antes que celos … y Aquiles en Troya (1747), the Penthesilea by Schoeck (1927) and King Priam of Tippett (1962). Concert works derived from the Iliad have been Bruch's choral Achilleus (1885), an overture Hector and Andromache by Henry Hadley (1894), no.1 (ʽHector's Farewell to Andromacheʼ) and no.4 (ʽAchilles Goes forth to Battleʼ) of Morning Heroes by Bliss (1930), and The Iliad of Dimitrios Levidis (1942–3) for narrator, tenor and orchestra.

The Odyssey, with the faithful Penelope at its core, and the wondrous adventures befalling the hero and his son Telemachus, has provided the basis for many operas. Among them are Monteverdi's Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria (1640), Il ritorno d'Ulisse of Jacopo Melani (1669), Circe and Penelope by Reinhard Keiser (1696, first and second parts of an Odysseus opera), the Ulysse of J.-F. Rebel (1703), Galuppi's Penelope (1741), Telemaco by Gluck (1765), L'isola di Calipso (1775) and Gli errori di Telemaco (1776) of Gazzaniga, Paer's Circe (1792), the Pénélope of Fauré (1913), The Return of Odysseus by Gundry (1940), an Odysseus by Hermann Reutter (1942), Circe of Egk (1948, revised as 17 Tage und 4 Minuten, 1966), and Ulysses by Michaelides (1951), who also wrote a Nausicaa ballet (1950).

Among concert works inspired by the Odyssey are the Syrens' Song to Ulysses by Benjamin Cooke (c1784), Bruch's choral work Odysseus (1872), an Odysseus symphony of Herzogenberg (1876), Zandonai's choral Il ritorno di Odisseo (1900–01), the prelude-cantata Iz Gomera (ʽFrom Homerʼ) by Rimsky-Korsakov (1901), Guido Guerrini's symphonic poem L'ultimo viaggio d'Odisseo (1921), the choral triptyque Ulysse et les Sirènes by Roger-Ducasse (1937), the Odysseus choral symphony of Armstrong Gibbs (1937–8), Jean Louël's cantata De vaart van Ulysses (1943), Impressions from the Odyssey for violin and piano by Frederick Jacobi (1945), and the epic symphony Ulysses and Nausicaa by Loris Margaritis.

Robert Anderson

Bibliography

H. Guhrauer: Musikgeschichtliches aus Homer (Lauban, 1886)

W. Leaf, ed.: The Iliad (London and New York, 1886–8, 2/1900–02/R)

C.M. Bowra: Tradition and Design in the Iliad (Oxford, 1930/R)

W.B. Stanford, ed.: The Odyssey of Homer (London and New York, 1947–8, 2/1958–9/R)

H.L. Lorimer: Homer and the Monuments (London, 1950)

G.S. Kirk: The Songs of Homer (Cambridge, 1962)

A.J.B. Wace and F.H. Stubbings, eds.: A Companion to Homer (Cambridge, 1963)

M. Wegner: Musik und Tanz (Göttingen, 1968)

C.M. Bowra: Homer (New York, 1972)

J.M. Snyder: ʽThe Web of Song: Weaving Imagery in Homer and the Lyric Poetsʼ, Classical Journal, lxxvi (1981), 193–6

M.L. West: ʽThe Singing of Homer and the Modes of Early Greek Musicʼ, Journal of Hellenic Studies, ci (1981), 113–29

A. Barker, ed.: Greek Musical Writings, i: The Musician and his Art (Cambridge, 1984), 18–32 [translated excerpts referring to musical subjects]

G. Danek: ʽ“Singing Homer”: Überlegungen zu Sprechintonation und Epengesangʼ, Wiener humanistische Blätter, xxxi (1989), 1–15

W.D. Anderson: Music and Musicians in Ancient Greece (Ithaca, NY, 1994), 27–57

For further bibliography see Greece, §I

Grove

~~~~~~~~~~~

Homeric hymns.

Poems addressed to various Greek deities, employing Homeric diction and composed in dactylic hexameter for solo recitation. The corpus of 33 poems, compiled at an unknown date and mistakenly ascribed to Homer, contains four long hymns ranging in length from 293 to 724 verses and dating from about 650 to 400 bce. The other 29 hymns are much shorter and were written somewhat later. Since the ancient sources refer to the hymns as prooimia (preludes) and several of the pieces contain a promise to sing another song, it has been suggested that the hymns once served as introductions to longer epic poems. But this opinion has been contested, especially in the case of the four long hymns. Little is known about the circumstances of performance, although the poems were probably recited in poetic competition at religious festivals. Thucydides (iii.104) describes the festival of Apollo at Delos, including two quotations from the hymn To Apollo. Most of the hymns consist merely of invocation and praise of their addressees, but the longer hymns are narrative and relate a myth central to the godʼs identity. The hymn To Hermes tells of the birth of Hermes, his invention of the lyre and his presentation of this newly crafted instrument to Apollo, with whom it was afterwards associated. Several of the hymns also contain references to the social and religious uses of music in the Archaic and classical Greek world.

Bibliography

T.W. Allen, W.R. Halliday and E.E. Sikes, eds.: The Homeric Hymns (Oxford, 1904, 2/1936/R)

A. Barker, ed.: Greek Musical Writings, i: The Musician and his Art (Cambridge, 1984), 38–46

G.S. Kirk: ʽThe Homeric Hymnsʼ, Greek Literature, ed. P.E. Easterling and B.M.W. Knox (Cambridge, 1985), 110–16

T.J. Mathiesen: Apolloʼs Lyre: Greek Music and Music Theory in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (Lincoln, NE, 1999)

Michael W. Lundell

Grove

~~~~~~

•Homer, Iliad

Showing 1 - 1 of 1 document results in Greek.

Homer, Iliad Less

(Greek) (English, ed. Samuel Butler) (English)

book 10, card 1: ... θαύμαζεν πυρὰ πολλὰ τὰ καίετο Ἰλιόθι πρὸ αὐλῶν συρίγγων τ᾽ ἐνοπὴν ὅμαδόν τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων. αὐτὰρ ὅτ᾽ ἐς

book 10, card 1: ... θαύμαζεν πυρὰ πολλὰ τὰ καίετο Ἰλιόθι πρὸ αὐλῶν συρίγγων τ᾽ ἐνοπὴν ὅμαδόν τ᾽ ἀνθρώπων. αὐτὰρ ὅτ᾽ ἐς

book 18, card 490: ... δὲ τάχα προγένοντο, δύω δ᾽ ἅμ᾽ ἕποντο νομῆες τερπόμενοι σύριγξι: δόλον δ᾽ οὔ τι προνόησαν.

book 19, card 387: ἐκ δ᾽ ἄρα σύριγγος πατρώϊον ἐσπάσατ᾽ ἔγχος βριθὺ μέγα στιβαρόν: τὸ μὲν

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper...:text:1999.01.0133&expand=lemma&sort=docorder

~~~~~~

•Homeric Hymns (ed. Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

Showing 1 - 1 of 1 document results in Greek.

Hymn 4 to Hermes (ed. Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

(Greek) (English, ed. Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

hymn 4, card 488: ... ἐπωλένιον κιθάριζεν: αὐτὸς δ᾽ αὖθ᾽ ἑτέρης σοφίης ἐκμάσσατο τέχνην: συρίγγων ἐνοπὴν ποιήσατο τηλόθ᾽ ἀκουστήν.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper...:text:1999.01.0137&expand=lemma&sort=docorder