tudorvolcano

Member

Sorry for writing in English, but my Greek is not good enough, and if I tried writing in Greek, I may commit a lot of mistakes, and make myself misunderstood. But feel free to answer in Greek if you wish, I think I'll still be able to understand.

Traditionally, our Church Fathers identified Ἦχος Πρῶτος with the Dorian mode of the Ancients.

But the problem is, how can that happen?

The scale of the Dorian tetrachord is traditionally said to be semitone-tone-tone, whereas Ἦχος Πρῶτος is Ἐλάσσων Τόνος - Έλάχιστος Τόνος - Μείζων Τόνος (10-8-12 in 72-EDO).

I think the solution to this problem lies in the history of our music.

In the old times, the Aulos was thought to have been evenly spaced.

Based on Kathleen Schlesinger's research in Arabic and Greek Music, the tuning for the Dorian Mode would be:

11/10 - 10/9 - 9/8 - 8/7 - 14/13 - 13/12 - 12/11

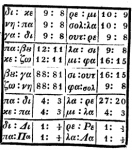

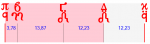

Which would look like this on a scale from Πα to Πα΄:

This looks very similar to the "equidistant" diatonic of Ptolemy:

Ptolemy's scale seems to be a harmonized version of the Dorian of the Aulos Modes, where Πα-Δι is a Perfect Fourth (4/3), and Πα-Κε is a Perfect Fifth (3/2).

Then, problem arises if we want to go below Ὑπάτη Μέσων (Πα), towards Λίχανος Ὑπάτων (Νη), that is the beginning of the Phrygian Octave species.

Normally, the Dorian Mode is not heptaphonic, but tetraphonic, meaning it follows the Wheel system. This can clearly be seen in the Enharmonic genus, where the ratio interval between Λίχανος Ὑπάτων and Ὑπάτη Μέσων is 9/8, when it should be 5/4, in an heptaphonic system.

Therefore, the distance between the Λίχανος Ὑπάτων and Ὑπάτη Μέσων in our diatonic is a Whole Tone (Μείζων Τόνος):

Problem arises when goes from the Dorian Mode on Ὑπάτη Μέσων (Πα) to the Phrygian one on Λίχανος Ὑπάτων (Νη).

The problem is that, whereas the Πα-Δι is in harmony, with a Perfect Fourth (4/3), the Νη-Γα interval is not, as the Γα-Δι is not a Whole Tone (Μείζων Τόνος). Therefore, Γα has to be lowered to allow for a perfect fourth, which brings us to the following scale:

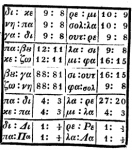

Which is in fact, exactly the tuning used by Al-Farabi: 9/8, 12/11, 88/81, and also the one used by our great teacher Χρύσανθος ὁ ἐκ Μαδύτων, as we see in the Μέγα Θεωρετικόν, on page 99:

Which is in fact, exactly the tuning used by Al-Farabi: 9/8, 12/11, 88/81, and also the one used by our great teacher Χρύσανθος ὁ ἐκ Μαδύτων, as we see in the Μέγα Θεωρετικόν, on page 99:

For his 12-9-7 tuning, it is in fact a result of logarithmic compromise, because he had to round up some intervals:

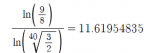

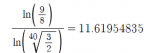

He divided the perfect fifth into 40 equal parts, meaning that 9/8 in his 40 equal division of the fifth would be:

Which would be round up to 12.

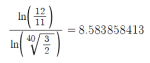

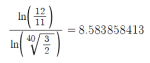

Then, the Ἐλάσσων Τόνος would be the in his system:

Which would be round up to 9.

As a result, the minimum tone would be calculated through simple arithmetics: 40-12-12-9=7

As for the tuning of the diatonic Dorian used by Archytas, 28/27 - 8/7 - 9/8, which would look like this:

It is in fact the same as our Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου Ἐνἁρμόνιος Βου Ὑφέσις:

In fact, it is very interesting that in the Middle Eastern maqam system, we have something very similar.

Our Ἦχος Πρῶτος / Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου in the 10-8-12 (or 9-9-12) intervals is called al-Maqam al-Bayati, whereas the 4-14-12 for Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου Ἐνἁρμόνιος Βου Ὑφέσις is called al-Maqam al-Bayati al-Kurd (which is often simplified to Kurd), showing us that Maqam Kurd is in fact a variant of Maqam Bayat, the same way we and the Ancients had the variants of a higher Πα-Βου interval and of a lower one.

The syntonic tuning 6-12-12 is just a tuning where Archytas' 1/3 tone is raised to a Pythagorean λεῖμμα, in order to allow for equal whole tones, giving us:

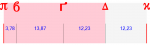

As for the tuning of the Patriarchal Comission in 1883, that is 12,23 - 9,65 - 7,99, it is not that different from the scales proposed by Al-Farabi and our 3 great Teachers. 9,65 vs 9,04, it is a very small difference, hard to notice, especially when singing at a very fast pace.

It was a result of descriptive investigation of the way our Psaltes sung. There will always be differences between theory and practice, especially because natural singing has small sensitizations, especially when doing special vocal techniques.

The Νη-Do equivalency was good as a descriptive tool, especially using the Do (C) as a base from which to tune the Νη and allow smooth singing, but it is not accurate from a historical point of view, as we see above.

Later attempts from scholars to conflate the Πα-Βου to Re-Mi were abusive, and not only detrimental to future research in the history of Byzantine and Ancient Greek music, but also damaging to many generations of Psaltes.

In Greece, this Westernization didn't damage the traditional Psaltes too much, but in Romania, in A.I. Cuza's time, and in communist times, with Nicolae Lungu, there was forced Westernization of our Byzantine intervals (imposed through severe persecution of our Psaltes) led to severe damage, that only now is getting healed; in fact, Psaltic Music was only kept alive thanks to a very small number of survivors of this persecution, that is people like Iustin Pârvu, from which most Romanian psaltes learnt, and where content was lacking, they had to copy Greek Psaltes.

Even though it ended up being a failure, we have to still remember the Western scholars Tillyard and Wellesz, which tried to "resurrect" Medieval Byzantine chant in Greece, where they tried to get rid not only of our very fine intervals, but also of our exegesis, our great signs and cheironomia, our rhythm, replacing it with with plainchant that they thought was the way Gregorian music was sung (in fact, there is a lot of research nowadays proving that 19th and 20th century approaches were flawed and that Gregorian music likely had a rhythm and was not plainchant, as previously believed). This was a huge attack from the Western scholars to our traditions, where they showed a clear Orientalist behaviour, trying to save ancient culture that was good from the "savages" who destroy it, that is us, as only they, the Western scholars, are the ultimate authority and the West is the "pure, uncorrupted" bearer of tradition, so they had to "restore" Byzantine music to "its old glory", because "Byzantine music couldn't have sounded strange to Western ears"; the situation in Western academic research is starting to improve, but we should always take their research with a lot of skepticism, and not let them impose their worldview on our traditions.

I am open to hearing comments, objections, to see where we can improve on our knowledge of Byzantine and Ancient Greek music.

Traditionally, our Church Fathers identified Ἦχος Πρῶτος with the Dorian mode of the Ancients.

But the problem is, how can that happen?

The scale of the Dorian tetrachord is traditionally said to be semitone-tone-tone, whereas Ἦχος Πρῶτος is Ἐλάσσων Τόνος - Έλάχιστος Τόνος - Μείζων Τόνος (10-8-12 in 72-EDO).

I think the solution to this problem lies in the history of our music.

In the old times, the Aulos was thought to have been evenly spaced.

Based on Kathleen Schlesinger's research in Arabic and Greek Music, the tuning for the Dorian Mode would be:

11/10 - 10/9 - 9/8 - 8/7 - 14/13 - 13/12 - 12/11

Which would look like this on a scale from Πα to Πα΄:

This looks very similar to the "equidistant" diatonic of Ptolemy:

Ptolemy's scale seems to be a harmonized version of the Dorian of the Aulos Modes, where Πα-Δι is a Perfect Fourth (4/3), and Πα-Κε is a Perfect Fifth (3/2).

Then, problem arises if we want to go below Ὑπάτη Μέσων (Πα), towards Λίχανος Ὑπάτων (Νη), that is the beginning of the Phrygian Octave species.

Normally, the Dorian Mode is not heptaphonic, but tetraphonic, meaning it follows the Wheel system. This can clearly be seen in the Enharmonic genus, where the ratio interval between Λίχανος Ὑπάτων and Ὑπάτη Μέσων is 9/8, when it should be 5/4, in an heptaphonic system.

Therefore, the distance between the Λίχανος Ὑπάτων and Ὑπάτη Μέσων in our diatonic is a Whole Tone (Μείζων Τόνος):

Problem arises when goes from the Dorian Mode on Ὑπάτη Μέσων (Πα) to the Phrygian one on Λίχανος Ὑπάτων (Νη).

The problem is that, whereas the Πα-Δι is in harmony, with a Perfect Fourth (4/3), the Νη-Γα interval is not, as the Γα-Δι is not a Whole Tone (Μείζων Τόνος). Therefore, Γα has to be lowered to allow for a perfect fourth, which brings us to the following scale:

For his 12-9-7 tuning, it is in fact a result of logarithmic compromise, because he had to round up some intervals:

He divided the perfect fifth into 40 equal parts, meaning that 9/8 in his 40 equal division of the fifth would be:

Which would be round up to 12.

Then, the Ἐλάσσων Τόνος would be the in his system:

Which would be round up to 9.

As a result, the minimum tone would be calculated through simple arithmetics: 40-12-12-9=7

As for the tuning of the diatonic Dorian used by Archytas, 28/27 - 8/7 - 9/8, which would look like this:

It is in fact the same as our Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου Ἐνἁρμόνιος Βου Ὑφέσις:

In fact, it is very interesting that in the Middle Eastern maqam system, we have something very similar.

Our Ἦχος Πρῶτος / Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου in the 10-8-12 (or 9-9-12) intervals is called al-Maqam al-Bayati, whereas the 4-14-12 for Ἦχος Πλάγιος τοῦ Πρώτου Ἐνἁρμόνιος Βου Ὑφέσις is called al-Maqam al-Bayati al-Kurd (which is often simplified to Kurd), showing us that Maqam Kurd is in fact a variant of Maqam Bayat, the same way we and the Ancients had the variants of a higher Πα-Βου interval and of a lower one.

The syntonic tuning 6-12-12 is just a tuning where Archytas' 1/3 tone is raised to a Pythagorean λεῖμμα, in order to allow for equal whole tones, giving us:

As for the tuning of the Patriarchal Comission in 1883, that is 12,23 - 9,65 - 7,99, it is not that different from the scales proposed by Al-Farabi and our 3 great Teachers. 9,65 vs 9,04, it is a very small difference, hard to notice, especially when singing at a very fast pace.

It was a result of descriptive investigation of the way our Psaltes sung. There will always be differences between theory and practice, especially because natural singing has small sensitizations, especially when doing special vocal techniques.

The Νη-Do equivalency was good as a descriptive tool, especially using the Do (C) as a base from which to tune the Νη and allow smooth singing, but it is not accurate from a historical point of view, as we see above.

Later attempts from scholars to conflate the Πα-Βου to Re-Mi were abusive, and not only detrimental to future research in the history of Byzantine and Ancient Greek music, but also damaging to many generations of Psaltes.

In Greece, this Westernization didn't damage the traditional Psaltes too much, but in Romania, in A.I. Cuza's time, and in communist times, with Nicolae Lungu, there was forced Westernization of our Byzantine intervals (imposed through severe persecution of our Psaltes) led to severe damage, that only now is getting healed; in fact, Psaltic Music was only kept alive thanks to a very small number of survivors of this persecution, that is people like Iustin Pârvu, from which most Romanian psaltes learnt, and where content was lacking, they had to copy Greek Psaltes.

Even though it ended up being a failure, we have to still remember the Western scholars Tillyard and Wellesz, which tried to "resurrect" Medieval Byzantine chant in Greece, where they tried to get rid not only of our very fine intervals, but also of our exegesis, our great signs and cheironomia, our rhythm, replacing it with with plainchant that they thought was the way Gregorian music was sung (in fact, there is a lot of research nowadays proving that 19th and 20th century approaches were flawed and that Gregorian music likely had a rhythm and was not plainchant, as previously believed). This was a huge attack from the Western scholars to our traditions, where they showed a clear Orientalist behaviour, trying to save ancient culture that was good from the "savages" who destroy it, that is us, as only they, the Western scholars, are the ultimate authority and the West is the "pure, uncorrupted" bearer of tradition, so they had to "restore" Byzantine music to "its old glory", because "Byzantine music couldn't have sounded strange to Western ears"; the situation in Western academic research is starting to improve, but we should always take their research with a lot of skepticism, and not let them impose their worldview on our traditions.

I am open to hearing comments, objections, to see where we can improve on our knowledge of Byzantine and Ancient Greek music.