I'd like to return to this topic with a question for which there is a direct, practical need for a solution.

In the Greek

Anastasimatarion and

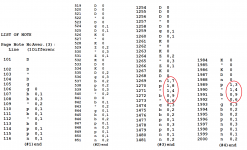

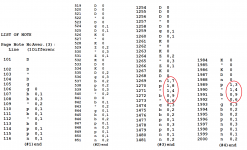

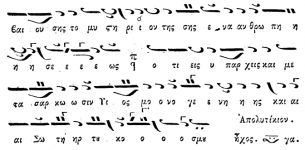

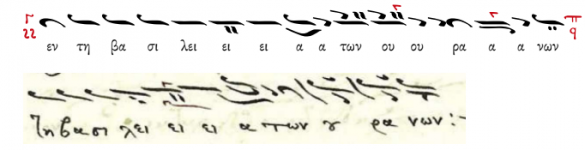

Doxastarion of Petros (a corpus which includes some 40-odd stichera in 1st Mode), there is not a single instance of a sticheraric melody in 1st Mode in which the text ends with an accent on the 2nd-to-last syllable (penult). All of these hymns have texts whose ending phrase can be accommodated by the following cadence (with some variation at the beginning).

In all the pieces I surveyed from those two works, every single hymn (except one) ended with the above formula. The single notable exception was the Holy Monday sticheron Ἐρχόμενος ὁ Κύριος, where a non-typical ending was used. This exception was notable not just for its use of an alternate formula when the above cadence would have (as far as I can tell) worked just fine, but also for the fact that the formula used for that ending cadence had been altered slightly to accommodate an extra syllable compared to the typical form which we find in the classical repertoire.

Thus, the works of Petros have been little help in finding an ending formula for text with an accent on the penult, due to the fact that, as mentioned above, not a single 1st Mode troparion in Petros'

Anastasimatarion or

Doxastarion contain an equivalent case that could be used as a precedent. The only thing close would be the end of Ἐρχόμενος ὁ Κύριος.

After surveying the works of Petros, I expanded my search to other reputable composers, and began surveying compositions by Manuel the Protopsaltis. In the book

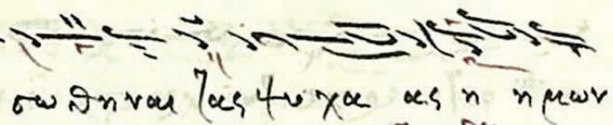

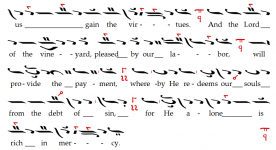

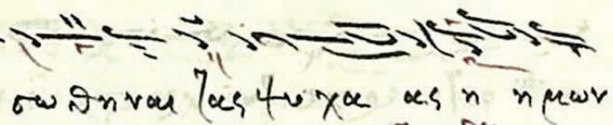

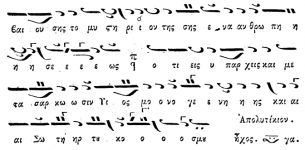

Sylloge Idiomelon kai Apolytikion, I noticed his setting of the third troparion at the Aposticha for the Transfiguration on August 6th: the hymn Τὸ ἄσχετον τῆς σῆς φωτοχυσίας. There, the text ends with an accent on the penult, and Manuel sets it with the following cadence:

When I first found this a number of years ago, I sent it to Papa Ephraim, and he added it to the ending cadences in the 1st Mode section of his formula book. (This line had previously only been found in the "medial cadences" section.)

I would be interested in any insight others (

@basil ) might have as to the use of this formula as an ending cadence in 1st Mode. By my estimation, it has the same "advantages" and "disadvantages" discussed above. To say it is rarely used would be an understatement, but that is partially just a function of the number of stichera in Greek that have an accent on the penult (in Petros'

Anastasimatarion or

Doxastarion, none). What would Petros have done if this textual ending pattern were more frequent? I'm hopeful that

@Laosynaktis can provide some insight into how common this textual ending pattern is in 1st Mode stichera more generally, not just the ones contained in the

Anastasimatarion or

Doxastarion, and what approach composers older than Petros took in setting such texts.

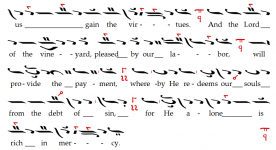

As a practical example of this problem, I've selected the Doxastikon at the Praises for the 4th Sunday of Lent. Below is how I have set the text; you'll notice that I followed Manuel's example in my choice of ending formula:

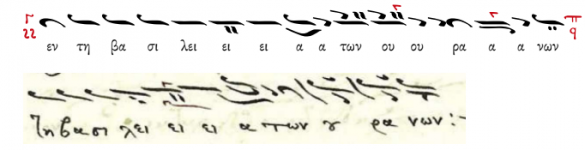

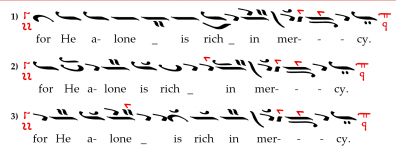

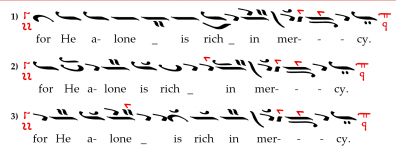

But other solutions that came to mind included the following:

#1 is the ending cadence from Ἐρχόμενος ὁ Κύριος, which has the advantage of being used by Petros.

#2 is something I made up; it evokes some of the more typical ending cadences in 1st Mode by moving up to Thi, but it does not end in the typical way.

#3 is also something I made up; it likewise sounds more like a typical ending cadence, but it blends that familiar beginning with the end of another common formula.

Thoughts and feedback are most appreciated.